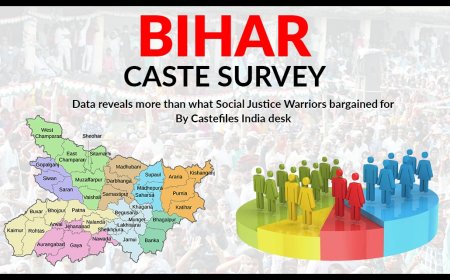

Bihar Caste Survey II - Is the Data Upsetting the Grand Caste Apple Cart?

This is the second in a series of explainers that Castefiles is publishing on the implications of Bihar's caste survey, and through it, the attempt to revive some of the worst forms of identity politics that have hobbled India over decades. In the tumultuous 1990s, the phenomenon of Mandal politics threatened to create permanent fissures within the Hindu society. By contrast, the Bihar Caste Survey 2023 and the corresponding hike in reservations to Government jobs and education institutions, have barely created any ripple in the caste interplay this time round. Hindu street's indifference to the move could well presage an era where caste plays a much-diminished role in Indian polity.

November 20, 2023: When a beaming Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar first released the caste survey for his state on October 2, there was palpable optimism within India's opposition camp, of which he is a key figure, that the move would pit the backward classes (BCs) and extremely backward classes (EBCs) against the upper castes, and be a game-changer going into the Parliamentary elections in 2024.

A few days after the survey showed that the share of BCs, EBCs, scheduled castes (SCs), and scheduled tribes (STs) had gone up in Bihar's population, Kumar followed up with a hike in reservations to government jobs and education institutions for these communities. The ploy was to offer them a bigger share of the pie to BCs and EBCs, who form 63 percent of Bihar's voters, as the survey data shows, and rally them behind the opposition I.N.D.I.A alliance.

Slim Pickings for Key Backward Groups

However, the wedge issue instead threatens to break up the unity of castes within the BC and EBC political ranks even before a grand caste coalition has coalesced. Any hike in job and education quotas can potentially energize the Caste Calculus and determine voting blocs. Caste leaders look to cash in on new-found voter loyalty and make their claims to a bigger share of political power by dividing Hindu votes.

The survey's findings have upset the calculations of powerful faction leaders amongst backward communities. Charged-up leaders of the Kushwaha community, considered to be one of the more prosperous and upwardly mobile agrarian backward castes, assembled in Kishanganj town of Bihar on October 9 to question the survey numbers. Their grouse - the population of the Kushwaha community had been under-reported, bringing their share of the population from an estimated 12 percent down to 4.21 percent, as reported in the survey.

Upendra Kushwaha, former Union minister and one-time party colleague of Kumar, has alleged foul play in the survey. Kushwaha, who now heads a regional outfit Rashtriya Lok Janata Party (RLJP), insinuated that the numbers of a certain `favored' community had been inflated in the survey. He was likely pointing at the increase in the numbers of the Yadav community, which is the single largest group in Bihar with a 14.26 percent share of the state's population.

Exclusive caste-based political outfits, floated by ambitious leaders from these communities, dot North India's political landscape. For these parties, success is a function of the population that forms their core voter base. Yadavs have benefitted well beyond their bare numbers, which, albeit sizeable, are nowhere near even a fourth of the total population in the two neighboring North Indian states of Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Bihar.

Any evidence that the numbers of a caste were lower than earlier believed, would greatly damage the bargaining power of the caste's leaders when it comes to their share in spoils of political power. There's no evidence yet of any fudging of caste numbers on the Bihar Government's part. After all, Kumar's own Kurmi caste has been reported in the survey to be a slim 2.87 percent of the state's population.

Highly Fragmented EBCs and Caste Calculus

A close scrutiny of the survey figures throws up some surprising facts. Taken together, EBCs are the largest grouping at 36% (4.70 crore or 47 million) of Bihar's population but on its own, not a single caste within the EBCs can cross even the three percent mark! Take the case of the Teli caste, which is not a politically vocal or visible community. While being the most numerous group within the EBCs, it is only 2.81 percent of the State's total population.

This granularity of the survey figures could wreck the calculus of caste-based outfits in UP and Bihar, the two states where managing caste dynamics is the key to electoral success. Vikassheel Insaan Party (VIP), an outfit of the Nishad community led by Mukesh Sahni in Bihar, would find its claims diluted as the community's numbers are shown to be 2.6 percent as against the six percent claimed by the outfit all along.

Any hard-nosed haggling for a share of power in Parliamentary and legislative elections going forward would inevitably run up against the reality of numbers thrown up by the caste survey. It could well give rise to a politics that's more fluid and unpredictable. Some signs of such unforeseen political outcomes are already visible.

Unlike the Mandal madness of 1990, there's been no outcry so far from the upper castes against the hike in reservations to government jobs and education institutions. That must be a cause of concern for the social justice warriors of Indian politics who were counting on caste disunity to wrack the Hindu society.